Maximising benefits of carbon pricing through carbon revenue use: A review of international experiences

Carbon pricing policies and their revenues are part of the tools available that can help fill the climate finance gap. With raising revenues from carbon taxes and emission trading systems (ETSs) that have tripled since the Paris Agreement, and an upward trend that could continue in the medium-term, ‘how to use carbon revenues’ has become a crucial question. This report, prepared as an activity of the EU-funded European Union Climate Dialogues (EUCDs) project, aims to inform policymakers and practitioners on lessons learned and ways forward on the use of carbon revenues, with a comprehensive approach based on a review of international experiences.

Ahead of the 2024 Spring Meetings of the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund, the Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC, Simon Stiell, stressed how important this and next year are for the achievement of the Paris Agreement and called for “a quantum leap in climate finance”. Indeed, with emissions required to peak before 2025, our window of opportunity is rapidly closing to keep 1.5°C within reach. More and better finance is urgently needed.

Carbon pricing policies and their revenues are part of the tools available that can help fill the climate finance gap. Revenues from carbon taxes and emission trading systems (ETSs) have almost tripled since 2015, and the upward trend could continue in the medium-term, raising questions on how they are and should be used in the future. To fill this knowledge gap and inform policy makers and practitioners on the lessons learned and ways forward on the use of carbon revenues, we reviewed experiences on carbon revenue use of 16 carbon taxes and 14 ETS that together make 94% of global carbon revenues.

Our study sheds light on the chain of decisions policy makers are confronted with to maximise benefits of carbon pricing through carbon revenue use. Several challenges are yet to be overcome related to transparency, accountability, and effective communication. But there are also good news. In 2022, over half of carbon revenues raised in selected jurisdictions had been used for climate and nature, and there is potential in key milestones of the international climate negotiations –notably the new climate finance goal at COP 29 and the revised national climate commitments at COP 30– for them to integrate a broader discussion on how to finance climate and development strategies, as part of financing plans for the transition.

This report is the final step of a broader process, carried out as an activity of the EU-funded European Union Climate Dialogues (EUCDs) project, with the aim of supporting a switch to a comprehensive perspective where carbon revenues are part of the implementation of low-carbon and climate resilient pathways.

Scope and methodology

The scope of the report concerns compliance carbon pricing instruments (CPIs) that directly put a price on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to encourage their reduction: direct carbon taxes (CTs) and emissions trading systems (ETSs).

Carbon crediting and indirect carbon taxes – such as fuel excise taxes – are not part of the scope. Hence, the term ‘carbon revenues’ for the purpose of the report refers to the financial resources generated through carbon taxes and ETSs by governments, that they can then use to pursue diverse policy objectives.

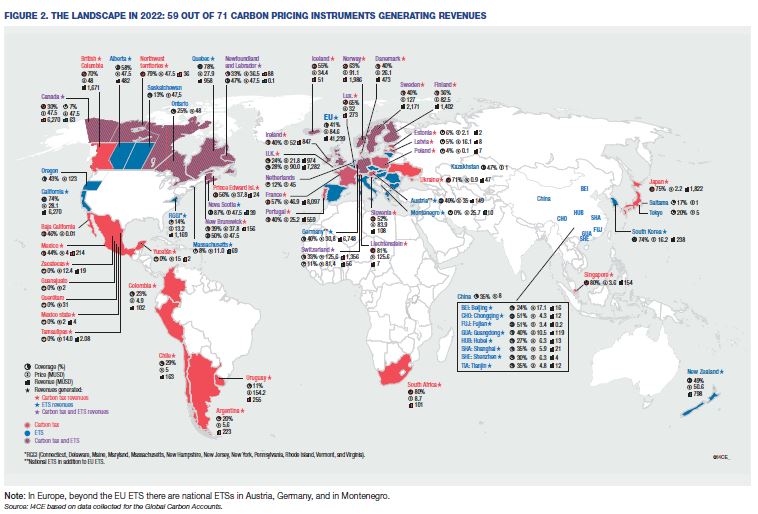

The term leaves out ’revenue forgone’ – the potential income that a government does not collect because of exemptions, reductions, or free allocations. The analysis on the use of revenues covers 30 CPIs in 27 jurisdictions that together make 94% of global carbon revenues. A wider scope is applied only to provide a global landscape of carbon pricing and carbon revenues based on I4CE data, complemented by World Bank data.

The main criteria for the selection of jurisdictions covered included revenue generation and data availability for the 2022 fiscal year, but also diversity; aiming to cover a large variety of practices, balancing size, geographical distribution, and share of ETS and carbon tax.

Key takeaways

- In 2022, 59 out of 71 carbon pricing instruments in place worldwide, generated around USD 95 billion.

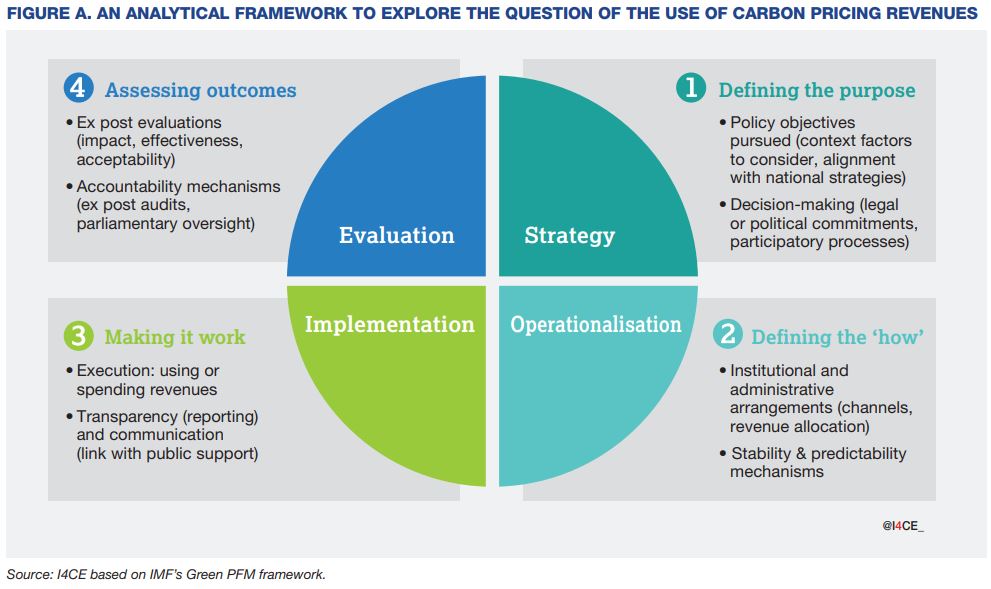

- Policy makers are confronted with a chain of decisions on the use of carbon revenues, with consequences in terms of effectiveness and acceptability of carbon pricing. These decisions can be seen as part of a four-step process, similar to the policy or budget cycle: strategy, operationalisation, implementation, and evaluation.

- Based on the review of international experiences on the use of carbon revenues in selected juridictions using this approach, the following key messages stand out for each of the four-steps:

1. To define policy objectives, decisions should be based on country contexts and priorities, striving for policy coherence and alignment with broader climate and development strategies. This step goes beyond the ‘earmarking’ or ‘no earmarking’ debate or the dilemma between having all revenues feed public budgets or serve a particular purpose. It entails seeing carbon revenues as part of the funding options that can help achieve a wide range of economic, social, and economic policy objectives in line with countries or jurisdictions’ needs and goals.

- Most jurisdictions – 21 out of 30 – have chosen to define policy objectives using some form of earmarking – strong as legal or soft as political commitments – for all or part of revenues.

- Out of the 14 ETSs studied, 10 have stated objectives for carbon revenue use, 9 of which include environmental objectives mixed with other socio-economic aims. An equal number of carbon taxes defined environmental and socio-economic objectives (9) with some mixing aims, while 8 had no aims defined for all (5) or part of the revenues (3).

2. To operationalize decisions on policy objectives for carbon revenue use, there is a need to assess trade-offs between different options and to design appropriate governance structures ensuring effective coordination. The use of the general budget as a channel is a legitimate choice that has often been supported by claims of flexibility and efficiency, yet its use should be coupled with tools to track expenditure – as green budget tagging– to avoid it becoming a sort of black box. A wide array of options of institutional and administrative arrangements –such as special-purpose funds, the tax system or even the social security system– should also be considered and analysed contrasting pros and cons against how they can serve stated policy objectives.

- At least one channel other than the general budget is in place to facilitate revenue use in 10 out of 14 ETSs, including special purpose funds, the social security system, and the tax system. In most carbon taxes – 9 out of 16, revenues are channelled solely through the general budget, yet some (3) pursue specific objectives and allocate revenues for these purposes through the budget process.

- Several measures to ensure stability and predictability of carbon revenues are observed, particularly in ETSs, such as market stability mechanisms, declining caps, phasing out free allocations, among others.

3. To implement decisions on objectives for carbon revenue use, transparency and effective communication have yet to improve, particularly on reporting actual uses. A lack of data and of clarity on methodological choices limits the possibility of assessing the real contribution of carbon revenues for the climate transition and other objectives, a key piece to evaluate the overall policy effectiveness.

- Around 52% of carbon revenues – close to USD47 billion – have been used for climate and nature, with half of the jurisdictions analysed dedicating all or part of revenues to this aim.

- Good practices on transparency and communication have been identified in 10 out of 27 jurisdictions covered based on their levels of publicly available information.

4. To evaluate the effectiveness of carbon revenue use and improve accountability, more ex-post evaluations and audits are needed, along with assessments on the link between revenue use and acceptability of carbon pricing. Few jurisdictions have taken this key step, which is very much needed to feed the overall process and make new decisions if needed for each previous steps based on the lessons learned.

- Accountability processes rarely land in the needed assessments of the impact of decisions on carbon revenue use, and few jurisdictions in general carry out ex-post evaluations or audits by external actors.

- Assessments of the impact of carbon revenue use in connection with the acceptability of carbon pricing are currently absent and should be included in formal evaluation processes. Outcomes in terms of acceptability of carbon pricing related to carbon revenue use are highly influenced by choices on communication strategies and political contexts.

- Good decisions on the use of carbon revenues can maximise benefits of carbon pricing and help ensure public support, but the potential trade-off with effective decarbonisation and the overall achievement of climate objectives must be considered to ensure policy coherence. Using revenues to support citizens or households that need it the most is a way to ensure the overall carbon pricing policy is socially fair, and supporting businesses to safeguard competitiveness is a choice that can be defended. Yet the devil is in the details, so how this is done and the consequences of these choices should be carefully analysed.

- Carbon revenues are already playing a role in the financing of the climate transition and there is potential for them to be further used to fill climate investment deficits. Around half of carbon revenues in selected jurisdictions –that represent 94% of global carbon revenues– have been used for climate and the overall environmental transition. Yet they are not often integrated in climate strategies such as NDCs and LTSs, which is a needed step.

- Carbon pricing instruments and their revenues should integrate a broader discussion on how to finance climate and development strategies, as part of financing plans for the transition. Key milestones of the UNFCCC process are opportunities for carbon revenues to join the broader discussion of how to finance the climate transition –notably the NCQG at COP 29, the revised NDCs at COP 30, and the revised NDCs at COP 30, and the Sharm el-Sheikh Dialogue on the operationalization and implementation of Article 2, paragraph 1(c) of the Paris Agreement.

- The landscape of carbon revenue use worldwide will certainly evolve in the years to come, as some jurisdictions have plans to change certain choices or have defined aims for the use of revenues of new carbon pricing instruments, which could strengthen their contribution to climate action and other development goals.

This activity is part of the European Union Climate Dialogues Project (EUCDs).