Is the transition accessible to all French households?

Report only available in French

An analysis of French state aid for investment in deep energy retrofits and electromobility

The transition requires guaranteed access to low-carbon solutions for all households

The issue of access to the transition for all households, in particular, for low- and middle-income households, has become central to the French public debate, as recently shown by the French President’s speech on ecological planning, when he referred to “an ecology that is accessible and fair, that leaves no one without a solution”. This growing awareness is particularly in response to the yellow vests protests: expecting households to take steps towards the transition if they have no access to solutions (electric cars, public transport, home insulation, heating upgrades) results in a rejection of transition policies and leads us collectively to a dead end.

What is the situation today? Is the transition accessible to all French households? This study does not attempt to give a comprehensive response to these questions. It focuses on the economic accessibility of solutions that require investments by households, in housing and mobility – specifically, deep energy retrofits and the acquisition of electric vehicles and charging points. A more in-depth approach to accessibility would imply also focusing on investments that are not made by households, such as in transport infrastructure.

We analyse state aid to foster household investment in the transition, for deep energy retrofits and electromobility, bearing in mind that this aid and its scales are currently being revised, with the process to end in late 2023. We focus on two main questions:

- How has aid for retrofits and electromobility evolved since its implementation, in terms of amounts and targeting?

- Is this aid enough to make low-carbon investments accessible to all French households?

More and more aid for investment is available to French households, in particular low-income and some middle-income households

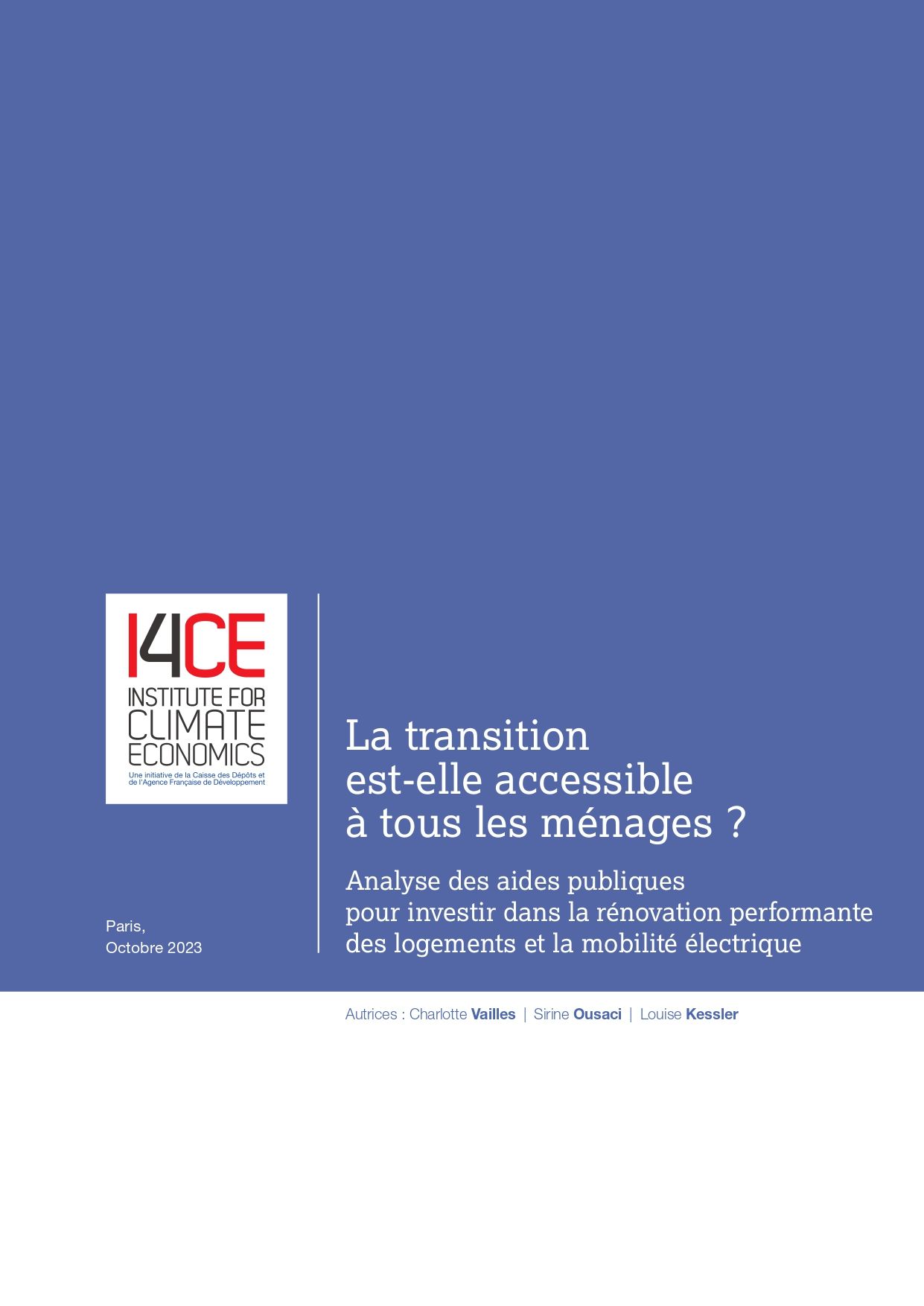

Since 2005, French aid programmes to support households in retrofitting their homes and buying electric vehicles and charging points have multiplied, and are increasingly indexed to household income (Figure A).

Over this period individual aid amounts have increased considerably. For the retrofitting of an individual house and the purchase of a new electric car and charging point, the maximum amount of aid a household can obtain has increased by approximately 160% between 2008 and 2023, from around 20 000 euros to 50 000 euros. By way of comparison, inflation over the same period was 17%.

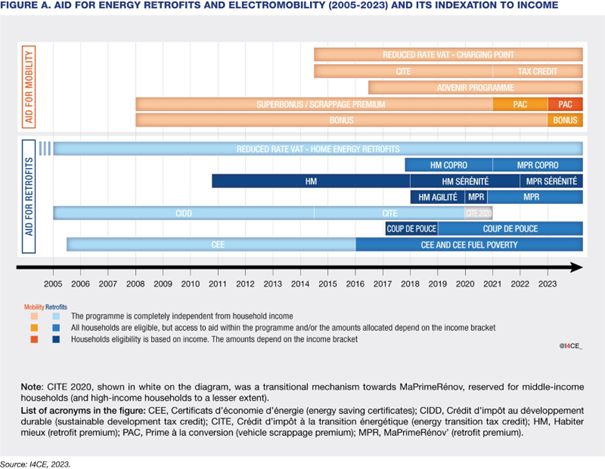

The increase in aid has been more significant for low- and middle-income households than for high-income households. Thus, at present, for a given situation, in other words for the retrofitting of a specific house and the purchase of a particular car, aid is around twice as high for low-income households as for high-income households. Most of the threshold effects that vary the aid amounts by several thousand euros each are situated within the middle-income category (see Figure B). For the different configurations in our study, aid accounts for between 25% of the investment (for high-income households) and 60% (for low-income households). For middle-income households in particular, aid accounts for between 26% and 55% of the total investment, depending on income and the configuration in question.

At present, the economic conditions to enable all French households to invest are not met

Although aid for energy retrofits and the purchase of electric vehicles has increased considerably in recent years, this does not guarantee that low-carbon investments are economically accessible to French households. The notion of accessibility as we consider it here covers the necessary – but not sufficient – economic conditions to ensure households invest in deep energy retrofits and electric vehicles.

Home deep energy retrofits

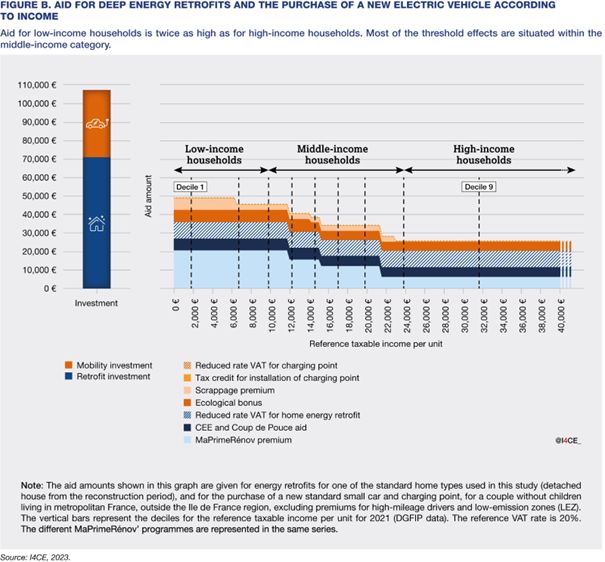

Despite the increase in aid observed in recent years, the out-of-pocket costs of retrofits for households, in other words the investment minus aid, which households finance using personal funds or by taking out a loan, still stands at tens of thousands of euros. This represents more than a year’s income for middle-income households, and 10 years or more for the lowest-income households (see Figure C).

The Eco-PTZ (zero interest eco-loan), whose ceiling has been increased to 50 000 euros for energy retrofits, is a financing solution to cover out-of-pocket costs. For households that succeed in obtaining this loan, the energy savings generated are sufficient in most cases (four of the six home types studied) to cover the monthly out-of-pocket repayments for all households.

However, obtaining an Eco-PTZ is associated with numerous obstacles for households, including complex administrative procedures and the debt load for low- and middle-income households. This debt load can reach 70% for the lowest-income households, and for those in the middle-income category, it typically exceeds 5%, a value considered to be the limit given that this loan is often added to an outstanding mortgage. In order to keep the debt load below this threshold, aid would need to be increased by more than 20% for low-income households and the bottom half of the middle-income category. This increase could be financed, among others, by shifting some aid from the highest-income households, without compromising the economic accessibility of retrofits for them, while reinforcing the other policy levers – especially regulations – to ensure these investments are actually made.

The forthcoming revision of MaPrimeRénov’ for 2024 brings some positive developments: the increase in aid for deep energy retrofits reduces the out-of-pocket costs for all households and for all homes. However, although the increase in aid is more marked for low-income households, financing for out-of-pocket costs still faces the obstacle of their debt capacity, with debt loads that often remain excessive for this income category. For middle-income households, the debt load falls below 5% – a positive step forward, which will need to be accompanied by efforts to remove the other obstacles to the deployment of the Eco-PTZ.

Electromobility

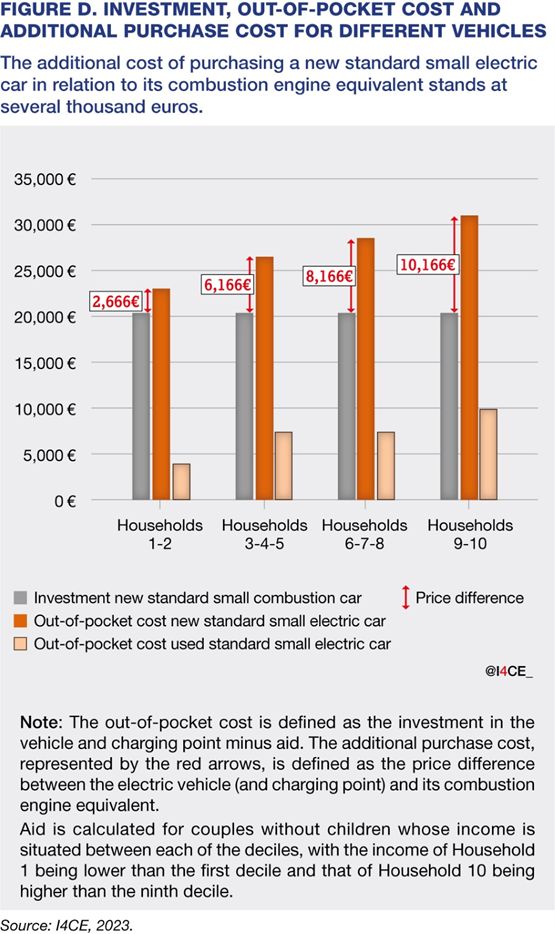

Purchasing a new electric vehicle poses a cash-flow problem for low- and middle-income households. Depending on the model, the out-of-pocket cost of a new car and the installation of a charging point ranges from around 10 000 to 40 000 euros. For a standard small car, it ranges from 26 000 to 28 000 euros for middle-income households, which represents between 65% and 130% of their annual income (see Figure D).

Households, especially those in the low- and middle-income categories, mostly purchase used cars. The out-of-pocket cost is far lower for a used electric car (around 7 000 euros for middle-income households), but the market is still underdeveloped in France. In early 2022, electric cars only made up 1% of the stock (around 400 000 vehicles) (France Stratégie, 2022).

Once the investment has been made, switching to electric cars helps to reduce households’ mobility budget, including fuel, insurance and vehicle maintenance costs. This reduction is more than 150 euros per month for a household that drives 13 000 kilometres per year, at energy prices in effect in the first half of 2023, which is a reduction of more than 50%. Because of the savings made on fuel costs, the purchase of an electric vehicle becomes cost-effective after just a few years for middle-income households.

Solutions for financing the out-of-pocket costs exist, including loans or leasing schemes, but they represent a considerable financial burden for households. For the standard small car studied, the energy savings made do not cover the leasing cost. With the energy prices in effect in the first half of 2023 and for a standard small car, aid would need to be increased by between 10 and 50% for low-income households and the lowest middle-income households to ensure energy savings cover the leasing cost, when the initial investment corresponds to the aid the household can receive.

The aid scales for the acquisition of new or used electric vehicles are currently being revised for 2024, but they are not expected to make a significant difference. One of the options considered is increasing the bonus by 1 000 euros for the bottom half of the low-income category. Despite this increase, the out-of-pocket costs for the purchase of a new standard small electric car would still correspond to more than a year’s income for the households concerned.

The social leasing proposal could be an interesting solution for low- and middle-income households, depending on the effective conditions for its implementation, which are still unknown at the time of writing this study. The reduction in electric vehicle prices expected for 2024, the increase in the ecological penalty set out in the budget proposal for 2024, and rising fuel prices should all contribute to making electric vehicles more and more attractive to high-income households.

Conclusion: beyond aid for investment, other obstacles will need to be removed to make the transition accessible to all French households

For deep energy retrofits and electromobility, in France the challenge for low- and middle-income households is to succeed in financing the out-of-pocket costs of investments, which are counted in years of income. The financing solutions that are currently on the table are not sufficient to make these investments accessible to low- and middle-income households, in particular because loans – even subsidised loans – face the obstacle of household debt capacity. An increase in state aid for low- and middle-income households therefore seems necessary to make the transition accessible, along with improvements to other financing solutions, such as zero-interest subsidised loans or the social leasing proposal.

It is also important to bear in mind that access to solutions for French households is a broader issue than their economic capacity to make investments. Other obstacles will need to be removed: where deep energy retrofits are concerned, training for artisans will need to be developed, along with the support available to households, access to rehousing solutions during retrofitting, and simplified administrative procedures; and where mobility is concerned, the network of charging points will need to be improved and households’ access to public transport networks and cycling infrastructure will need to be facilitated.