Climate stress tests: what co-benefits can we expect for transition financing

Since their introduction, climate stress tests have taken a lot of space in the public debate. Put in the spotlight by supervisors and the NGFS, their primary objective is to encourage banks to integrate climate-related risks into their activities and to carry out an initial assessment of the banks’ capacity to deal with these risks.

The public debate around climate stress testing has quickly focused on the methodological difficulties of developing a framework for analysing climate-related risks or developing appropriate transition scenarios. This study seeks to move away from this focus by looking at another aspect. Beyond their contribution in terms of assessing the exposure of financial institutions to climate-related risks, and although this is not their initial objective, climate stress tests could in fact also have indirect impacts on transition financing.

In its report, I4CE attempts to identify what possible co-benefits climate stress tests may have on transition financing, as well as their limits in this regard. The findings presented are based on an ex-post analysis of the initial lessons learned by French banks and supervisors from these exercises.

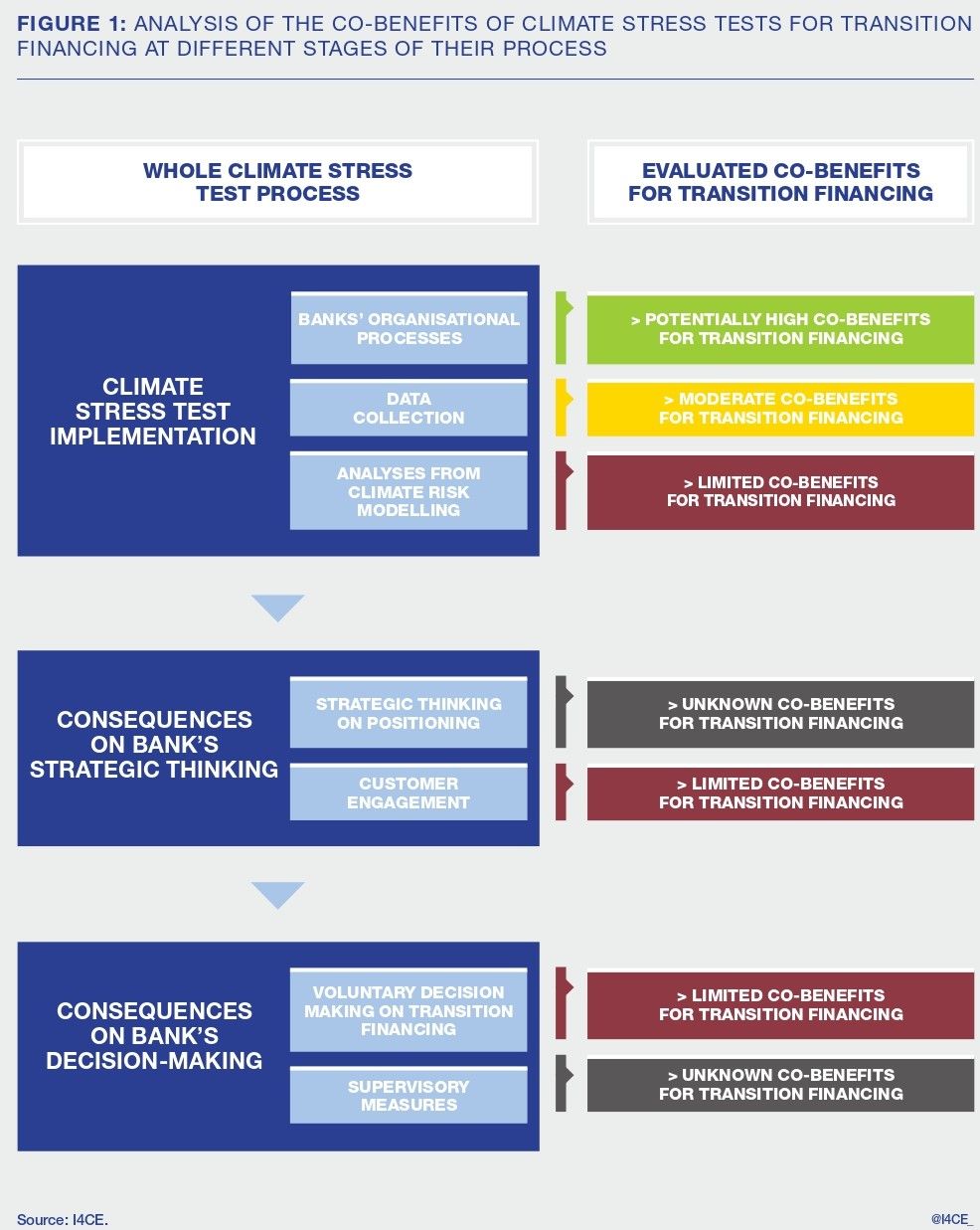

In this study, the impact of climate stress tests is examined throughout their process, from the operational processes of their implementation to the impact they may have on banks’ strategic thinking and decision-making concerning transition financing.

The most significant co-benefit of climate stress testing: a process that mobilises banks’ internal teams and supervisors around climate-related issues

The successive climate stress tests implemented by the supervisors on French banks have been very useful in enabling an initial integration of climate issues into the banks’ organisational processes and governance. In particular, these exercises have led to the implementation of trainings on climate issues among the banking teams, they have strengthened the coordination between them and they have allowed significant mobilisation of financial and human resources on these subjects. They have also enabled the supervisors of the financial system to increase their expertise in these topics.

Yet, the more the banking teams are trained and coordinated on climate issues, from the bank’s executive committee to the operational teams, the more they could potentially be in a position to take decisions in favour of financing the transition.

It should be noted, however, that while these conditions are necessary for the development of relevant bank strategies, they are not necessarily sufficient to actually trigger a shift in banks’ financial flows towards transition finance. This will depend on whether banks are able to identify financial opportunities in doing so, due to their improved understanding, or whether regulatory requirements provide incentives.

Climate stress tests enabled however a fragmented analysis of climate-related issues, moderating or limiting the co-benefits of these exercises on transition financing

First of all, these exercises required banks to collect a certain amount of climate data on their counterparties. These processes have been of partial use depending on the types of data requested. The collect of the Environmental Performance Certificates (EPCs) of the buildings of banks’ counterparties, for instance, is essential for if banks wish to participate in the financing of the transition in the real estate sector. However, the collection of greenhouse gases emissions data on banks’ largest counterparties should have a limited impact on transition financing. This data does not provide any insight into the transition potential of the counterparties or into the financing needs related to the implementation of their transition plans.

The analyses deriving from the modelling exercises also had a limited impact on the ability of banks to finance the transition. They presented numerous difficulties in assessing the impact of the transition in the real economy, and they did not manage to sufficiently grasp the dynamics of the transition and the various risk transmission channels. Yet, for banks to be able to participate in the financing of the transition, it seems very important that they have fully integrated all the specificities of these dynamics, in order to take decisions accordingly.

Climate stress tests have then played a limited role in the development of banks’ climate strategies and decision-making processes

Although climate stress tests have prompted some strategic thinking among banks, especially about their positioning, they have not yet led to major changes in their decision-making processes related to providing transition finance. They did not change their investment or financing criteria as a result of the climate stress tests.

The main reason for this is that they do not consider the results of climate stress tests to be sufficiently reliable to be incorporated into decision-making processes. The difficulty in demonstrating the financial materiality of climate-related risks, generated by the uncertainties linked to the modelling of adverse transition scenarios and their impacts, currently hinders the direct use of climate stress test results in banks’ investment and financing decisions.

The difficulty of these exercises in demonstrating environmental materiality as well, in the sense that they are not able to differentiate companies that are on a credible transition pathway from those who are not, is obviously also an obstacle to transition financing.

As a consequence, even if it is still too early to estimate the full indirect impacts climate stress tests may have over time, it seems unlikely that they will ever succeed on their own in actually triggering an important shift in transition financing. To achieve this objective, climate stress tests should be accompanied by other instruments that allow banks to better understand the transition dynamics of their counterparties in order to better support them in the transition. Banking transition plans could be effective solution for that, since they should rely on banks’ counterparties transition plans, and allow the banks to better understand how they can accompany their counterparties in the transition. They could then have a significant role in filling in the missing pieces needed to put banks in a position to provide transition financing and thereby play an active part in the quest for an orderly transition.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement N°101003884.