Approaches to meeting the Paris Agreement goals: options for Public Development Banks

Options for Public Development Banks

Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, several public development banks (PDBs) have responded with structured approaches to align their operations with the Agreement’s expectations (as described in Section 1). However, many PDBs, particularly those in emerging markets and developing economies, are yet to adopt an approach to align with the Paris Agreement (i.e., Paris alignment).

As entities whose investment mandates are established by the Parties to the Paris Agreement (i.e., national governments), PDBs have specific obligations derived directly from these Parties’ commitments to act across all policy and regulatory frameworks under their jurisdictions, including for state-owned or state-mandated institutions and agencies. Accordingly, PDBs are expected to operate in a manner that supports the achievement of the Paris goals. More specifically, they are obligated to integrate their activities within the Agreement’s implementation mechanism by providing financial, technical, and capacity building support that is entirely consistent with national low-emission climate-resilient development pathways.

Paris alignment is defined in this context as a response to the specific Paris Agreement expectations vis-a-vis PDBs’ integration within the Agreement’s means of implementation (1). To be Paris-aligned, a PDB must orient its operations to provide financial, technical, and capacity-building support that is entirely consistent with recipient countries’ low-emission climate-resilient development pathways.

This concept of Paris alignment differs fundamentally from approaches that focus on reducing a financial institution’s financed emissions on a trajectory consistent with the Agreement’s overall temperature objectives or that suggest the adoption of a set of climate actions commonly observed by financial institutions.

While neither of the alternative Paris alignment concepts above is sufficient to facilitate full alignment of PDBs, some of their components have been used as benchmarks for alignment.

This report aims to provide actionable insights for PDBs seeking to align their activities with the objectives of the Paris Agreement by evaluating the main approaches adopted by financial institutions and identifying the key operational benchmarks used to support the implementation of these approaches.

Approaches to mainstreaming Paris Agreement objectives

On the other hand, private financial institutions have typically adopted the “portfolio-level net-zero” approach, which aims to achieve net-zero financed emissions at the portfolio level. While there is substantial variation in how this approach is implemented, it generally entails an accounting of financed emissions in an institution’s portfolio, then setting a year-on-year emissions reduction trajectory benchmarked against Paris temperature goals. In addition, private financial institutions have also adopted fossil fuel exclusions and counterparty engagement strategies to advance their mitigation efforts.

The portfolio-level net-zero approach is far narrower than the project-level alignment approach because it does not obligate consistency with low-emission climate-resilient development. Accordingly, the implementation of a portfolio-level net-zero approach alone would not achieve Paris alignment for PDBs.

This divergence in approaches results from the fundamentally different expectations that public and private financial institutions face under the Paris Agreement (see Section 1) and the distinct incentives driving their investment activities. Despite this divide, PDBs should at least be aware of how private-sector clients and partners are approaching climate action and, in some cases, may even benefit from strategically adopting aspects of the portfolio-level net-zero approach themselves (see Section 2.4).

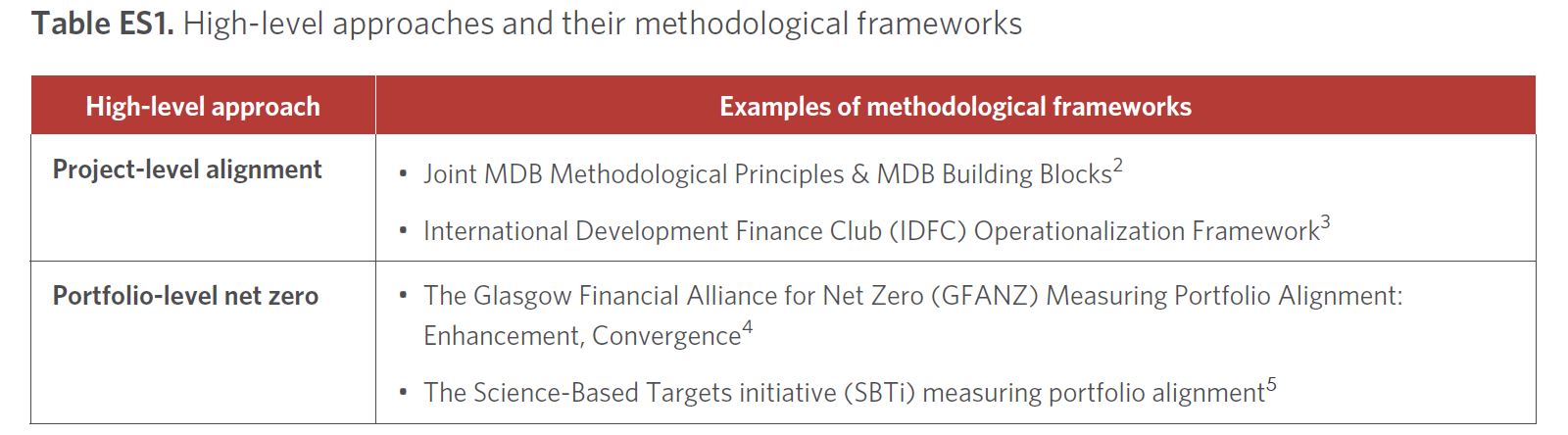

While there are myriad ways in which these high-level approaches are implemented across institutions, they are guided by a handful of key methodological frameworks, as shown in Table ES1.

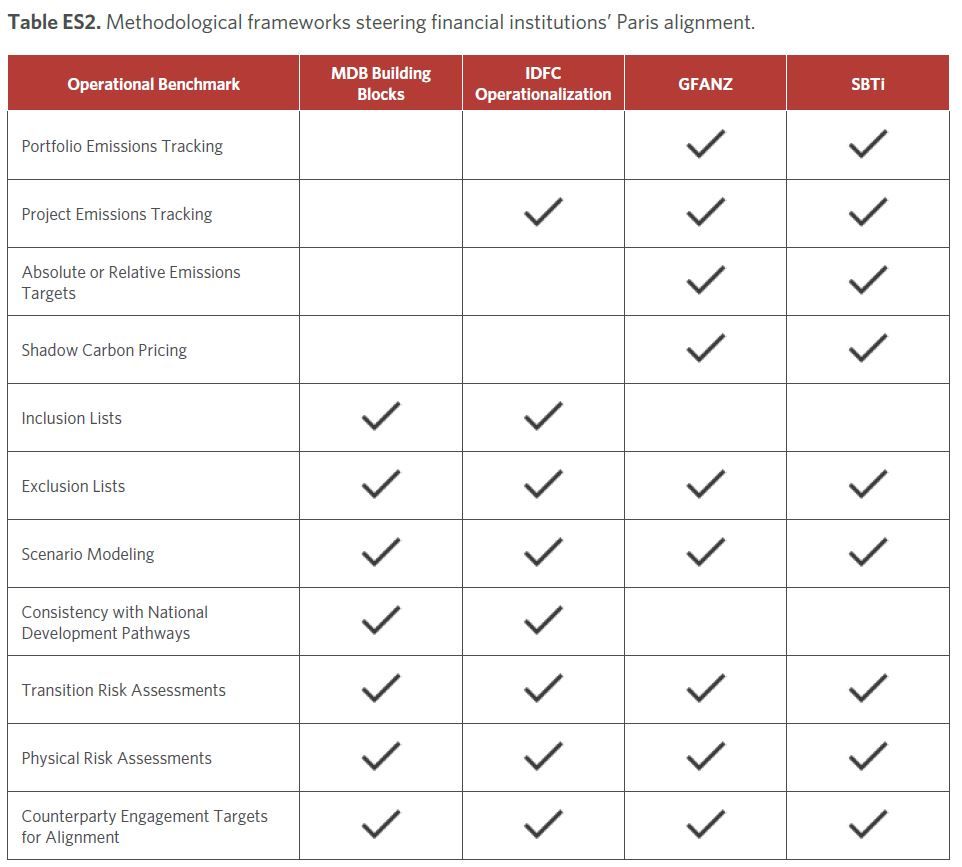

Alignment approaches’ use of operational benchmarks

To effectively advance all of the Paris Agreement goals, PDBs should select and integrate operational benchmarks that are both practical and impactful. The MDBs’ joint Paris alignment approach (the MDB building blocks) offer a foundational approach for PDBs, focusing on improving understanding of their role in achieving the Paris goals and incentivizing the maximization of their impacts to this end. In addition, the concept of “do no harm” should be instilled as a minimum condition for PDB financing activities. PDBs should also seek to use benchmarks to maximize synergies between climate and other objectives in order to make efficient use of human and material resources and ensure applicability to the broad universe of PDBs.

Each of the various operational benchmarks offers distinct strengths and weaknesses for PDBs, depending on the bank’s client base and existing level of Paris alignment. While benchmarks can provide transparency, accountability, and measurable guidelines, employing the wrong ones can create operational challenges or conflict with existing priorities or mandates. Additionally, the associated technical capacity and resource requirements may become a hindrance.

Key takeaways from case studies

To better understand the methodological frameworks for Paris alignment approaches (e.g., the MDB building blocks) and the operational benchmarks adopted by financial institutions, this report presents six case studies examining the practices of five PDBs and one private financial institution.

These case studies have yielded the following key takeaways:

- All five PDBs featured have taken a project-level approach to Paris alignment, using multiple operational benchmarks to complete their assessments.

- Several PDBs have also integrated a net-zero portfolio approach; two use this to facilitate engagement with private-sector counterparts, while another uses its approach to align institutional activities more closely with the national climate goals of the countries in which they operate.

- A strong program for counterparty engagement is crucial to the implementation of either approach.

- PDBs that are active across multiple geographies and sectors require wider operational benchmarks to contextualize their alignment assessments.

Conclusions and recommendations

Our analysis of Paris alignment approaches, their constituent operational benchmarks, and key takeaways from case studies has led to the following conclusions and recommendations. These aim to guide PDBs in developing and improving their alignment approaches at various stages of implementation.

1. Project-level alignment forms the foundation of PDB support for Paris Agreement goals.

1a: PDBs that have not yet adopted a comprehensive alignment approach should start by outlining a project-level alignment approach to ensure that their future projects support the national low-emission climate-resilient development pathways of the countries in which they operate.

1b: Assessments of project-level alignment should use operational benchmarks that are as context-specific as possible, ideally incorporating context-specific aspects such as national development priorities, sectoral transition pathways, and transition and physical risks.

1c: In countries where national low-emission climate-resilient development pathways are yet to be established or lack detail, PDBs can engage national governments to develop long-term strategies and scenarios, along with corresponding financing plans, thereby connecting the project-level approach with the whole-of-institution approach.

2. Integrating operational tools from the portfolio-level approach can provide strategic benefits for banks that work closely with the private sector or operate in tandem with other governmental agencies on mitigation.

2a: PDBs that work frequently with private-sector clients should assess whether many of these clients have set transition planning and emissions targets (if relevant in the context of their operations).

2b: PDBs in markets where transition planning and emissions targets are common – or may soon become so due to new regulations, industry standards, or institutional peer pressure – should consider integrating tools from the net-zero portfolio approach to facilitate productive engagement with the transition approaches of private-sector clients and partners.

2c: PDBs that incorporate a portfolio-level net-zero approach must follow best practices for setting interim emissions targets, maintaining reporting and verification, and engaging with counterparties on emissions reduction. These practices should be communicated to clients and replicated by them where feasible.

2d: PDBs that have an advanced Paris alignment approach focused on providing transition finance and transformative impacts, as well as activities aimed at supporting the systemic and structural changes needed for a low-emission transition, may find that the net-zero approach contradicts their climate policies and even their development mandates, as limiting portfolio emissions would also limit their investment in transition activities.

3. Paris alignment is an evolving and ongoing process that requires consistent board and senior management support.

3a: PDB governance bodies need to fully engage in the planning and operationalization of a Paris alignment approach to ensure that it is properly implemented and clearly understood across all sub-departments and processes. This underscores the importance of board and senior management ownership of the process.

3b: Furthermore, PDB governance bodies, leadership, and internal operations teams should formally review their Paris alignment approaches on a regular basis to identify any possible gaps and revise benchmarks against any changes to low-emission climate-resilient development pathways and the latest science-based targets.

4. Stakeholder engagement is key to developing and implementing a Paris alignment approach.

4a: As PDBs develop alignment approaches, they should encourage clients and other external stakeholders to align their internal operations and client relations with suitable alignment approaches.

4b: Where financing activities fail to achieve the desired objectives of aligning clients’ goals with those of the Paris Agreement, PDBs should continue to engage with clients and other external stakeholders, especially their boards and shareholders. This is particularly important for PDBs that work with corporate clients, to track progress towards corporate transition goals.

4c: PDBs should also engage with each other through networks such as Finance in Common, which facilitate the sharing of best practices for the development and implementation of alignment approaches.

5. Further research can seek to identify which investments and support activities deliver systemic or transformative impacts.

5a: PDBs that have already implemented a comprehensive alignment approach can seek to develop methods and operational benchmarks to assess impacts. These can go beyond the direct mitigation or adaptation benefits generated by projects to assess the potential for systematic or transformative outcomes that support the largescale changes needed to transition to low-emission and climate-resilient economies.

5b: Similar to alignment, impact assessment will require context-specific information that accounts for differences in national low-emission climate-resilient development pathways.

1: The specific expectations facing PDBs under the Paris Agreement are summarized in Section 1.1.

2: World Bank, 2018

3 Lütkehermöller et al, 2021

4 GFANZ, 2022

5 SBTI, 2022