Adapting French buildings to heatwaves: what do we know?

Context : This study was conducted as part of the development of the next French National Climate Change Adaptation Plan. Thus, the elements presented and the conclusions drawn were made within the French context. However, certain costs, methodologies, and conclusions presented may be directly useful as such in the European context or for other member states.

To address the growing impacts of heatwaves on economic activities and populations, the adaptation of the building sector is becoming a new imperative. While the question of “how” to adapt has been the subject of numerous studies, the question of “how much” has so far received little attention. To move forward on this issue, we present in this report:

- An overview of current knowledge regarding the costs of adapting the building sector to heatwaves.

- The methodology we used to estimate the additional costs of adapting to heatwaves, based on available information and discussions with experts.

This analysis enables us to draw seven lessons and one recommendation:

1 – The absence of a shared and consensual common framework is one of the main obstacles mentioned by sector stakeholders who wish to embark on an adaptation process. Although they increasingly identify summer comfort as a key issue, sector stakeholders currently lack standardized weather files aligned with the French reference warming trajectory (TRACC based on a warming of 4°C on average for mainland France by 2100), as well as technical references, specifications and labelling processes for adaptation.

Recommendation

Set up and facilitate working groups to produce a common reference framework for adaptation to climate change in buildings, similar to the ongoing CAP 2030 initiatives that anticipate the next regulation on new construction.

> Building this common reference framework is emerging as the next critical step for adapting existing buildings to heatwaves.

2 – Recent events have shown that buildings are ill-adapted, leading to significant impacts that are likely to increase if nothing is done. While heatwaves do not directly damage buildings, they do impact economic activities and the health of people living, studying or working indoors. These impacts are already significant: at the European level, recorded productivity losses stand at between 0.3% and 0.5% of GDP in years with heatwaves, although it is difficult to determine the share of these losses attributable to buildings. In France, between 2015 and 2020, estimated health impacts were between 22 and 37 billion euros. As the climate continues to warm, the exposure of the building stock will increase. At just 2°C warming in mainland France (by 2030 according to the TRACC), nearly half of all buildings will already be highly or very highly exposed, rising to almost all of the building stock at +4°C. Dense urban areas will be particularly affected and cities that currently have low exposure could become highly exposed in the future. If nothing is done to adapt, the economic and health impacts of heatwaves will also increase. On a European scale, they could reach several GDP points by the end of the century in the most exposed countries and cause 30 more deaths than at present.

3 – The prevailing response to the evolution of this problem is to install air conditioning. This is the reactive measure seen in most cases and already represents investments estimated at around 3.5 billion euros annually for housing. If this pace continues, almost all of the building stock could be equipped by 2050. Often described as maladaptation, the mass deployment of air conditioning raises questions about the externalities it generates : increased electricity consumption, greenhouse gas emissions and especially a significant rise in outdoor temperatures in urban areas, which could reach several degrees.

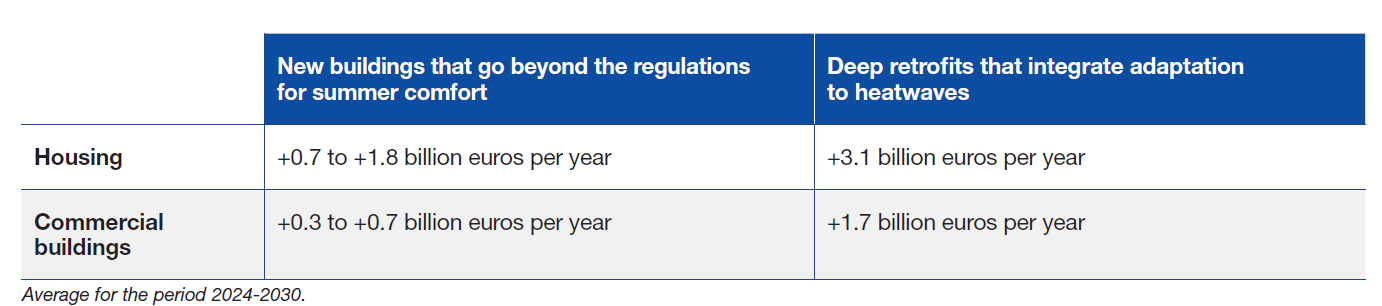

4 – Other adaptation solutions are available and can be integrated into existing planning dynamics. These solutions are well documented and can mostly be used in combination with planned operations. Where new construction is concerned, they entail going beyond current regulations, which do not yet take account of climate projections. For the existing building stock, adaptation needs to be integrated into the energy retrofitting policy, which aims to renovate the majority of the stock by 2050 (according to the French National Low-carbon Strategy). The first step should be to redirect investments towards deep retrofits, which are the most effective for summer comfort and which currently lack almost nearly 27 billion euros per year to meet targets. This adaptation effort represents an additional cost, which we have estimated in this study at between 2% and 5% for new construction and at 10% for retrofitting compared to operations without adaptation. In relation to the public and private investment needed to achieve carbon neutrality objectives, this would represent additional requirements of 1 to 2.5 billion euros for new construction and 4.8 billion euros for retrofitting.

5 – These additional investments could prove insufficient beyond a certain level of climate warming. Few prospective studies exist to date. However, the initial available information shows that for some climate zones (particularly the Mediterranean region), it will become increasingly difficult to cope without air conditioning from the middle of the century (+2.7°C). But these studies also agree on the effectiveness of adaptation solutions and urge the adoption of a sequenced approach, meaning first implementing other solutions before considering air conditioning.

6 – Adapting to heatwaves will not be limited to a series of works on buildings, as adaptation solutions are only effective if used correctly. User awareness and behaviour are therefore crucial. More broadly, a systemic and integrated approach will guarantee the resilience of economic activities and populations facing heatwaves. At the city level, territorial policy must be consistent with adaptation challenges and attach importance to the quality of the social fabric, thus avoiding situations of isolation. It must also ensure the health system and emergency services are sufficiently robust to limit the health impacts of heatwaves. Finally, for economic actors and public services, other initiatives can be implemented to address heatwaves, such as installing water points or adjusting working hours.

7 – Further research is needed to enhance understanding of the economic needs for adaptation in buildings. This includes: improving knowledge about the consequences of disrupting or closing an essential public service during heatwaves; better determining the effectiveness and limitations of adaptation solutions at the building stock level; and enhancing knowledge about their costs. Exercises of this type have been conducted abroad and could be replicated in France by sector experts.