Here’s to an impactful new year for financial reform

2023 will be busy with many events organised to address different parts of the financial architecture reform, including a Paris Summit in June. Alice Pauthier from I4CE tells you more about this agenda and identifies two conditions for a successful reform process. First, it has to be led by countries’ financing needs… wheras we are still lacking a granular analysis of countries’ investment needs for a sustainable development. Second, it has to be guided by the objective of maximising the impact of public finance. What we should count is the impact of public finance on the transition and not only volumes.

In just one year, a global consensus was created on the need to reform the global financial architecture. Following up on Mia Mottley’s memorable speech at COP26 highlighting that “failure to provide climate finance is measured in lives and livelihoods being lost”, the government of Barbados, developed the Bridgetown Agenda for the Reform of the Global Financial Architecture. The objective is to drive financial resources towards a sustainable low-GHG and climate-resilient development while addressing the cost of living crisis and the developing country debt crisis. At COP27, Barbados received the support of countries including France, whose President announced the organization of a Summit to be held in June 2023. It also received support from the broader international community, as highlighted in the Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan with the mention of the need for “a transformation of the financial system”.

In 2022, concrete proposals were already being discussed to reform the World Bank and other Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs). MDBs have a specific role in the global financial architecture as they should in theory be able to support countries in addressing current crises while contributing to their sustainable development over the long term. However, their resources are limited. In an effort to help address their current limitations, several organisations have developed proposals for reform. An Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance presented proposals for an MDB reform calling for “both a significant expansion in the scope of their activities and a major increase in the volume of their financing”. The G20 created an independent panel who developed recommendations to help MDB shareholder governments better understand whether MDBs can lend more without posing a threat to their long-term financial integrity. Building on these recommendations, Germany and the US, backed by 10 countries, including all of the G7 group, handed a joint proposal for “a fundamental reform of the World Bank” to its management. The World Bank responded with the publication of an “evolution roadmap” that should support next spring’s discussions with its Board on the Group’s evolution. Building on these proposed and planned MDB reforms, 2023 should see reforms of the entire finance architecture, including revisions of the role of all public finance institutions.

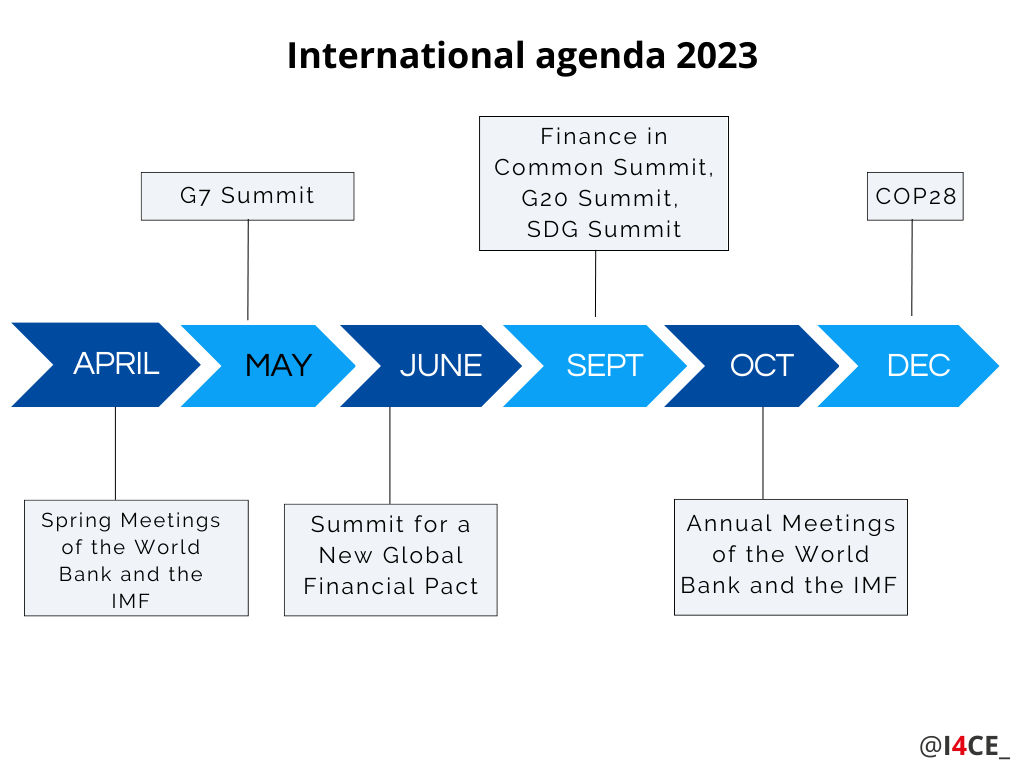

Beyond the Paris Summit, 2023 will be busy with many events organised to address different parts of the financial architecture reform agenda: the Spring Meetings of the IMF and the World Bank as well as the G20, the G7 and the Finance in Common Summit and COP28. These events are all opportunities that must be seized to change the trajectory of development finance and make the system fit for current and future challenges. Capitalising on over a decade of work on financing the transition in France, Europe and developing countries, I4CE has identified two minimum conditions for a successful reform process led by countries’ financing needs for a sustainable development and guided by the objective of maximising the impact of public finance for the transition of economies.

To be successful, the reform of the global financial architecture should give priority to defining the country financing needs.

The last time development finance received that much attention was 2015 when the climate and development agenda converged around the need for country-based and integrated approaches for a sustainable development. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda then acknowledged the importance of taking into account the three dimensions of sustainable development – economic, social and environmental – together. To do that, the same year both the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Agenda and the Paris Agreement have promoted a bottom-up and country-driven approach, with each “government setting its own national targets guided by the global level of ambition but taking into account national circumstances”.

In 2023, this bottom-up approach remains the key condition for a successful reform of the global financial architecture. The IMF recalls that “the desirable role of the public and private sectors in financing mitigation and adaptation investments is context specific. The role of public and private sector financing varies across countries depending on country-specific characteristics and the local economic and institutional context”. And, according to the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Brookings Institution: “the starting point for a big investment push must be strong country leadership and actions. All countries need to set out well-articulated investment programmes to stimulate recovery and transformation anchored in sound long-term strategies to deliver on development and climate goals. These programmes need to be translated into concrete pipelines of projects and supported by a favourable investment climate.”

However, we are still lacking a granular analysis of countries’ investment needs for a sustainable development. To achieve this, each country may take the following steps – with the support of international actors when needed:

- develop inclusive long-term strategies and sectoral plans, to achieve climate and broader sustainable development objectives to identify the country-specific socio-economic transitions that will occur over the long term;

- Translate these strategies into investment and financing needs over different time horizons (macro-economic component);

- draw up an overview of current financing and additional financing needs to be met in order to:

- identify the role of public and private sector actors as well as national and international actors;

- identify the sources (national budget, carbon revenues, green bonds, domestic capital markets, international climate finance, etc.) and existing financing mechanisms that could be used;

- identify innovative financing mechanisms and public-private collaboration to fill the remaining gaps.

Climate finance landscapes can be a key tool for these analyses. The dissemination of these analyses/methods/tools could be key to inform and help public finance institutions identify where their support is needed and where they should prioritise their efforts. This is why I4CE contributes to these analyses.

Public financial resources are precious, particularly in times of crisis. The reform of the global financial architecture should ensure that public finance is channelled to where it is needed the most.

Even though we are still lacking a granular analysis of financing needs for the transition, one point is clear: public financial resources alone won’t cover financing needs. While part of the reform agenda will be focusing on the different ways of increasing volumes of public finance, it will also be necessary to focus on how to make the most efficient use of these resources. To that end, what we should count is the impact on the transition, and not volumes of finance. And this impact should be measured taking into consideration countries’ specific needs for public finance.

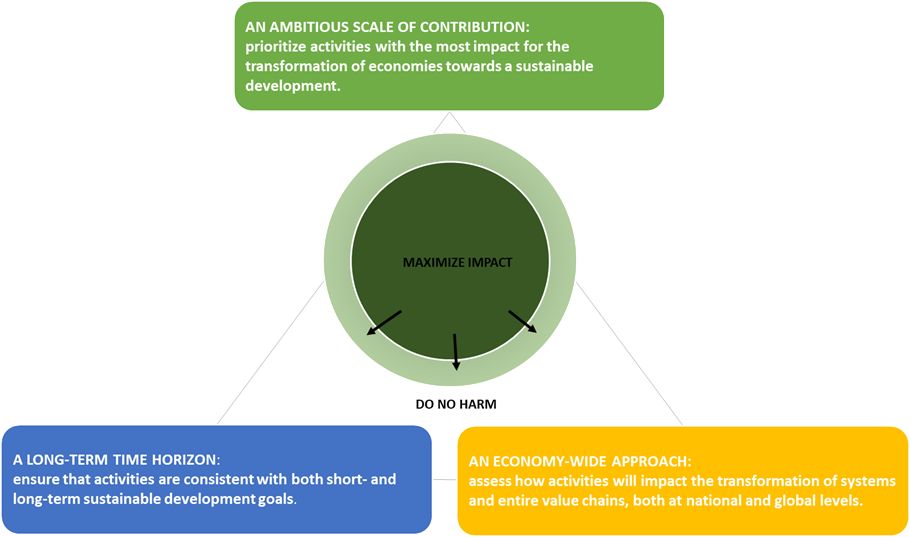

Public Finance Institutions (PFIs), whether they be international, regional or domestic, play a key role in directing public finance. Today, a clear paradigm shift is needed to optimise the role of Public Finance Institutions in financing the transition: Individually, PFIs need to shift from a focus on volumes of climate financing to a focus on their real impact on the transformation of national economies. As PFIs’ resources are limited, financing sustainable activities like an additional windmill is not enough. They need to focus their efforts on activities that will have the most impact on the transition of economies, like the capacity building of national governments in the development and implementation of sustainable development plans. To maximize their impact, they should ensure that all their activities are consistent with sustainable development goals, assess how their activities will impact the transformation of systems at the national and global level and prioritize activities on the basis of their impact.

Collectively, analyses and coordination are needed to identify which PFI is the most well placed and equipped to answer countries’ financing needs. To be successful this reform should be comprehensive. It can’t only focus on multinational development finance that represents less than 10% of total public finance operations. The role of national finance institutions and subnational finance institutions that represent respectively 70% and 21% of operations according to latest research from INSE and AFD should also be a key part of the discussion. The current increasingly crowded and fragmented system should be reformed for more pragmatism, and efficiency. The most concessional resources should be allocated carefully where needs are high, such as for the adaptation of least developed countries. The development of the above-mentioned analyses of countries’ financing needs could represent the building blocks for a discussion on the role of public and private as well as national and international finance institutions and the different financing and non-financing instruments they can use to respond to these needs. In some regions, national public banks will have a decisive role to play, while in others, international finance will be absolutely necessary.

Reforming the international public finance architecture is ambitious. It represents a broad and complex item on the international agenda this year. But it is also an opportunity that we can’t miss if we want to remain on track to achieve climate and sustainability goals.