Understanding deforestation processes in Brazil to avoid the tipping point

The fires in the Amazon have put the challenge of deforestation back on the political and media agenda, responsible for about 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC, 2014). I4CE’s Clothilde Tronquet discusses the causes of deforestation and measures that could slow it down and avoid reaching a point of no return.

From deforestation to pasture, from pasture to crops: the sequence of deforestation in the Amazon

Fires in the Amazon are part of a deforestation pattern that combines illegal logging, livestock and agro-industrial crops; involving successive land conversions over time.

Forests are first degraded by logging operations. This stage can take several years, with forest degradation occurring first through the extraction of the noblest woods, then the cutting of smaller trees and finally of bare vegetation (Instituto de Economia Agrícola, 2015).

The surfaces are then burned to complete the clearing process during the dry season from June to November, with a peak in the number of fires in September (Global Fire Emissions Database). These fire clearing processes are therefore not natural events: they are man-made (IPAM, 2019). In addition, climate change, by increasing the vulnerability of ecosystems, makes these fires more frequent, intense and difficult to stop (L De Faria & al., 2017).

The cleared areas become cattle pastures, generally characterized by low stocking rates and very low productivity (Ferreira & al., 2014). Finally, after several months or years, the pastures are transformed into crops, including soybeans. Before being used for soybean cultivation, areas can go through intermediate stages of maize and rice cultivation (Rivero, Almeida, & Ávila, 2009). It should be noted that several fire cleanings can occur to maintain pastures or crops.

Whether on private property or public forests, the vast majority of deforestation is illegal. It is also important to note that part of deforestation is part of land grabbing dynamics. Indeed, a quarter of recent deforestation concerns public forests, which are called “without designation” because they are not subject to specific protection, unlike conservation areas or indigenous reserves (Azevedo-Ramosa & Moutinho, 2018). Once cleared, these lands are often illegally occupied (Brown & al., 2016) pending to be legalized (Brito & al., 2019).

The importance of the political factor in Brazilian deforestation

Satellite monitoring systems of the National Institute of Space Research of Brazil (INPE) have established that the number of hectares deforested and forest fires detected in Amazonia increased dramatically in 2019 compared to the previous year: respectively 683,300 ha deforested in 2018/2019 , representing +49% compared to 2017/2018 and 65,518 fires over the period from 01/01/19 to 01/09/19, or +86% compared to 2018 (INPE).

However, these figures must be put in perspective over time to understand their economic and political causes.

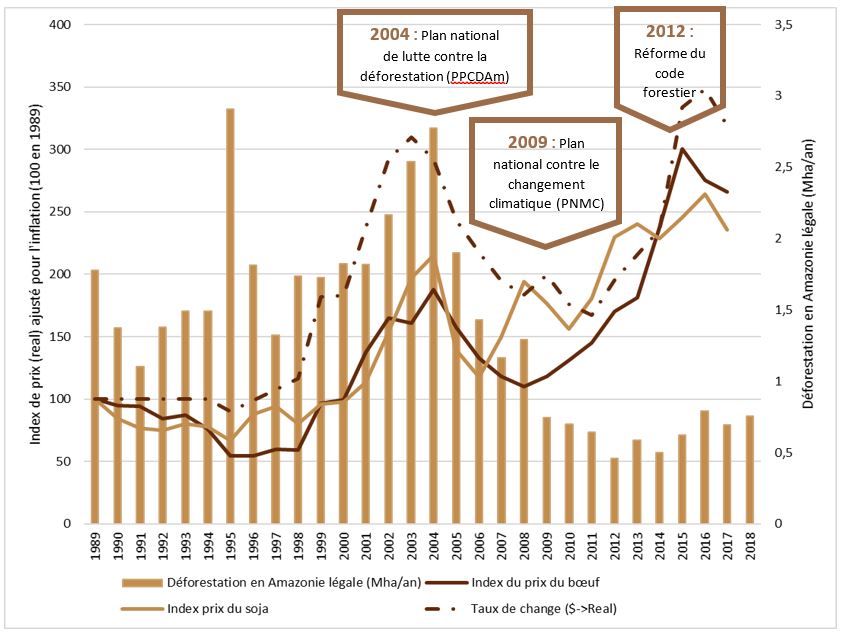

Brazilian deforestation has long been correlated with agricultural commodity prices and the real/dollar exchange rate, which more or less favours exports. From the mid-1990s to 2004, beef and soybean prices rose, as did the number of hectares deforested. Prices and deforestation declined over a few years until 2006-2008 (Dias Paes Ferreira & Bragança, 2015). However, since that date, the correlation has been visibly broken.

Deforestation in the legal Amazon (Mha/year) – Source: I4CE based on Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) data

Deforested areas continued to decline until 2014, before rising up again, while soybean prices rose throughout the period. It should be noted that it is possible to decouple agricultural production from deforestation through sustainable agricultural intensification. Over the period 2004-2014, for example, a considerable decrease in deforestation occurred while the volumes of soybeans produced in Brazil only increased. This increase in production has occurred mainly on areas previously used as low-productivity pastures (Carneiro Filho & Costa, 2016), illustrating what many scientists and NGOs have been demonstrating for years: it is possible to increase production without further deforestation, through increased productivity and the exploitation of existing degraded pastures (Moutinho, Guerra, & Claudia, 2016). Deforestation is therefore not inevitable, even in the context of the growth of the soybean market in Brazil, for which China and Europe are the main customers , in the form of grains, soya meal for animal feed, oil or biofuel.

Consequently, economic factors are insufficient to explain the evolution of the deforestation rate. Over the last fifteen years, its variations correspond to two distinct political periods in Brazil:

- The remarkable decrease in deforestation rates between 2004 and 2014 reflects the Brazilian government’s proactive policies in terms of forest protection: extension and strengthening of protected areas, structuring and strengthening the effectiveness of control systems and sanctions, but also private sector commitments (moratorium on soya) (Assunção, Gandour, & Roch, 2012) (Nepstad, 2014).

- The resumption of deforestation since 2014 has been less studied, but it seems to be the result of successive weakening of laws against deforestation, the means allocated to its monitoring, and sanctions for offenders (InfoAmazonia). In particular, the reform of the forest code in 2012 led, through changes in categories, to a reduction in protected areas and restoration obligations (Soares-Filho & al., 2014). In addition, land policy has allowed the legalization of land grabbed (Brito & al., 2019), thus contributing to send a signal to illegal occupants that they would not be prosecuted or could subsequently be exonerated.

This analysis reminds us, on the one hand, that current deforestation rates remain much lower than those of the early 2000s and, on the other hand, that the resumption of deforestation is the result of developments that started well before the election of Jair Bolsonaro, the weakening of policies to combat deforestation having been initiated under the mandate of Dilma Roussef (under pressure from ruralists) and continued under the government of Michel Temer. Jair Bolsonaro is only intensifying this deconstruction of environmental law, which he considers to be an attack on economic development. In addition, he also sends signals in his public statements that serve incentives to break environmental law for non-compliance with environmental laws and the protection of indigenous populations, indirectly influencing deforestation.

To reduce deforestation, multiple levers to be aligned and activated by the public and private sectors

The Amazonian experience shows us that it is possible to implement effective conservation policies, but also illustrates the vulnerability and reversibility of these efforts. National public policies are crucial against deforestation, particularly those related to land tenure, monitoring and sanctions. Their mere legislative existence is not enough and they require resources to be allocated for their implementation.

Other actions must be taken, and not only in countries where deforestation is at work, in particular demand policies that integrate agriculture and food issues:

- Private sector commitments against deforestation have increased since the early 1990s in the form of general declarations, company commitments, codes of conduct or sector certification, such as the moratorium on soya in the Amazon and international initiatives such as the Forest 500 or the New York Declaration on Forests. To be effective, these approaches must be transparent and traceable. In this sense, the Accountability Framework Initiative offers common guidelines for aligning commitments related to deforestation.

- Consumer countries must also reduce their imported deforestation. In France, in 2018, the government launched a strategy to combat imported deforestation covering both supply and multisectoral demand, considering, among other things, a “0 deforestation” label if existing certifications prove inadequate. This approach also involves increasing national protein autonomy in order to cover the demand for animal feed.

- Finally, at the individual level, the reduction in meat consumption has a considerable potential. Indeed, the mitigation potential of a change towards a more plant-based diet and therefore less land intensive diet amounts to up to 8 GTéqCO2/year, and complements the mitigation potential of deforestation reduction (up to 5.8 GTéqCO2/year (IPCC, 2019). In this sense, an I4CE publication provides a literature review of food-related mitigation policies.

Beware of the point of no return

Deforested areas are accumulating, further weakening the Amazon’s carbon sink and biological richness. It is currently estimated that 20% of the Amazon has already been deforested (one million km2). The first models estimated that 40% of deforestation in the Amazon would be the threshold of no return at which the rainfall patterns in the region would be modified and drought would increase significantly, thus affecting the entire functioning of the Amazon ecosystem. More recent research estimates that this “tipping point” is in fact around 25% (Lovejoy & Nobre, 2018).