After Bonn and towards COP 29: the battle on finance and the role of financing plans for the transition

Tense climate negotiations just ended in Bonn with limited progress on finance and the revised climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

This contrasts with the ambitions expressed during the opening ceremony of the sixtieth sessions of the subsidiary bodies (SB 60) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Simon Stiell –Executive Secretary– highlighted the need to “make serious progress on finance, the great enabler of climate action” and to aim for bolder, broader and inclusive third generation Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs 3.0) that “can serve as blueprints to propel economies and societies forward and drive more resilience”.

Despite initial high expectations, on two key milestones of the UNFCCC process for this and next year, no or only little progress was made. Negotiations on the first one, the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance aiming to update the existing commitment by developed countries to mobilise finance for developing countries, got stuck when the time came to deal with the crucial question of the numbers. The NCQG must be defined by the end of this year at COP29. Also, during discussions on the second milestone related to the NDCs 3.0, to be submitted in 2025 informed by the outcomes of the first global stocktake (GST) that was presented at COP 28, countries lacked ambition.

The challenge is now for COP29 to find solutions and forge pathways forward. Financing plans for the climate transition are a key piece of the puzzle that can contribute to the interconnected discussions on the NCQG and the NDCs 3.0. The concept of financing plans which is compatible with, and can inform country platform approaches that have gained momentum in recent years. These plans can help ensure NDCs 3.0 function as investment roadmaps for an effective use of climate finance and implementation of country climate strategies. Here is why.

What do we mean by financing plans?

Financing plans are tools governments can use to reconcile different priorities while fostering an efficient and effective use of public finance. They can contribute to ensure that all financial flows are directed towards national low-emission and climate-resilient pathways, in line with national climate and development objectives. Moreover, they can shed light on the way forward on the country platform approach proposed by several actors to shift from the project-by-project approach and beyond the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) model, seeing by some as “long on promise but short on progress”.

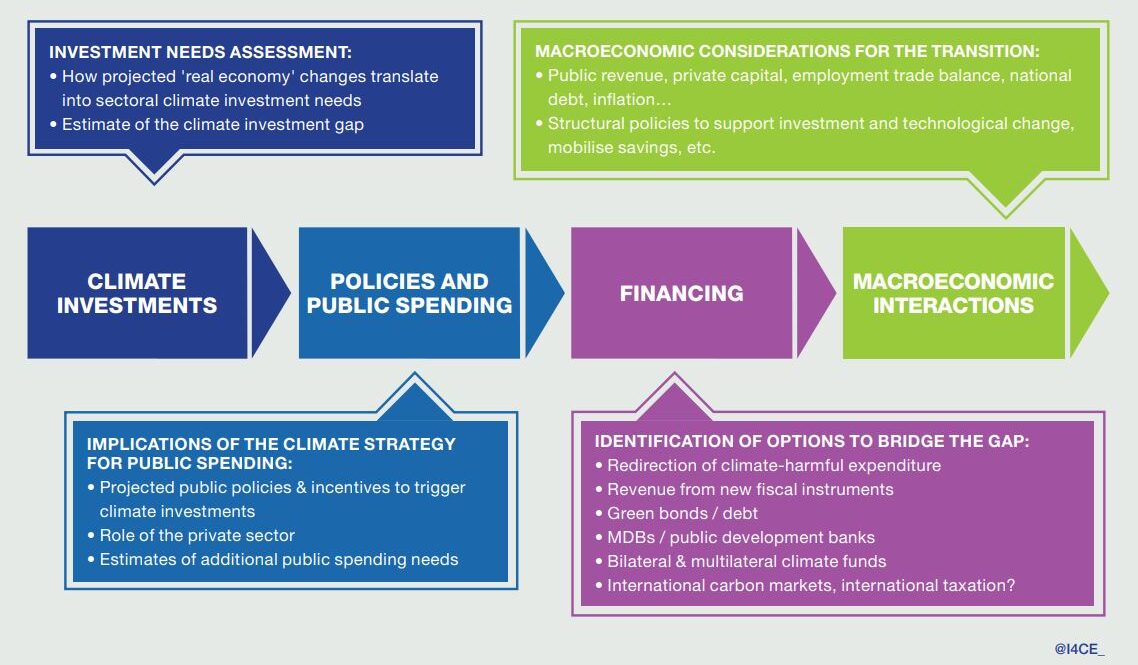

A financing plan helps translate climate goals into an investment roadmap. With a country’s strategy – an NDC or a Long-Term Strategy (LTS) – as the starting point, these tools help define short- and medium-term investment needs and estimate the investment gap, with a whole-of-economy approach. With these inputs as a basis, they also help define policies needed to trigger those investments and identify funding options to fill the gap, while integrating macroeconomic considerations. Our view of the key components of these plans is illustrated below.

Financing plans: key building blocks

Source: I4CE 2024.

And although all countries can benefit from such plans, they are even more relevant for developing countries that are confronted with limited fiscal space to address climate and development priorities.

With a financing plan at hand, governments can give a clear signal to the private sector and international funders as to where public efforts should be supported and/or supplemented. And this is where the connection with the NCQG starts.

Financing plans and the NCQG: ensuring climate finance based on needs

There is a general agreement on the fact that the NCQG must be based on the needs and priorities of developing countries, and from a floor of USD 100 billion –previous commitment. In emerging and developing economies (excluding China), these needs have been estimated at around USD 2.4 trillion per year by 2030. Thus, no matter how ambitious the NCQG ends up being, it will not be enough to meet those growing needs, and an effective use of these vital resources is essential.

When guided by a financing plan aligned with a country’s climate targets, international climate finance can truly serve those needs and priorities and be used more effectively.

The NCQG process can hence benefit from and should support the development of financing plans. The integrated perspective they provide would bring clarity as to where financial support needs to go, help prioritise and ensure impact towards the achievement of climate goals. Yet many countries will need support to come up with these plans, as well as to implement them.

Financing plans and the NDCs 3.0: aiming for climate investment roadmaps

NDCs embody efforts to reduce emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change that each country must undertake and communicate, as established in article 3 of the Paris Agreement. In line with this article, NDCs should be designed as comprehensive instruments including targets for mitigation, adaptation, finance, technology development and transfer, and capacity building; and complying with transparency guidelines. They are expected to show progress over time, which is why they are required to be updated every five years, while recognizing the need to support developing country Parties for effective implementation.

The new round of NDCs is the opportunity to finally arrive to the comprehensive instruments they were meant to be, integrating all means of implementation and particularly finance. For developing countries, the challenge would remain nationally focused. While for developed countries, considering their current and future commitment to provide and mobilise climate finance for developing countries, their NDCs should ideally include their commitments of financial support.

NDCs 3.0 should then also function as an investment plan that countries can use to guide their public finance management decisions, their policies and international commitments, and to access climate finance matching their needs.

Assessing countries’ progress on financing plans for the transition

With increasing recognition of the key role of finance as an enabler of climate action, countries around the world have taken steps forward to develop tools to finance the transition pathways set in their NDCs and LTSs. Yet not all countries are moving at the same speed on this issue. Some may need support to arrive to even the first step of defining climate investment needs, while others may be more advanced on the path and could provide valuable insight to others based on their experiences.

At I4CE, we have embarked on a journey to contribute with an assessment of countries’ progress towards the development and implementation of financing plans for the transition. Our plan is to track this progress for each of the building blocks that in our view should be addressed in such plans. The table below shows an example of some macro indicators we are exploring to come up with a benchmark of G20 + 6 countries towards COP 29 and beyond.

With this work, we aim to provide insight on the current state of things and way forward, and to contribute to the interconnected discussions on the NCQG and the NDCs 3.0, with key recommendations based on the lessons learned.

The first GST recognized the world is not on track to meet the objectives set in the Paris Agreement, and these milestones may be the last opportunity to revert the trajectory. A successful NCQG is equivalent to keeping a lifeline for many countries, while progressive, more ambitious, and comprehensive NDCs are the needed cure that can take us out of the emergency room. In their intersection, financing plans are needed to ensure effectiveness in the use of climate finance provided and mobilised, and in the implementation of country climate strategies.

This blogpost was written by Diana Cardenas Monar, Research Fellow at I4CE within the ‘Steering Tools for Financing the Transition’ team, with the important contribution of Gracia Rahi, Research Assistant, for the elaboration of the country assessment table. If the above arguments have sparked any ideas, we would really value your thoughts. We welcome all feedback and expressions of interest to support this ongoing work and others related to financing plans for the climate transition.