Climate change and residential real estate: what are the risks for the banking sector?

Residential real estate in France is a key target for transition policies and the sector is highly exposed to climate risks. While home loans account for almost 85% of outstanding household loans in France, it is legitimate to ask how climate risks are passed on from the real estate sector to banks. This article, written with the Banque de France, investigates the exposure of residential real estate to present and future climate risks as well as their transmission to the lending activities of the banking sector.

An increasing exposure of residential and homeowners to climate risks

French residential real estate is already suffering the consequences of climatic phenomena, such as flooding, major fires or clay soil movement caused by alternating periods of rain and drought. Direct damage to property may require repair, or even the relocation of its inhabitants. In today’s climate, the whole territory is exposed to these risks but in heterogeneous ways. Taking into account climate change and trends in housing stock, the cost of climate-related damage could double by 2050, reaching 143 billion euros (France Assureurs, 2021). And that’s not counting the indirect impacts of climate affecting access, use and attractiveness of housing.

Residential real estate is also a key sector for national energy-climate policies. French policies focus in particular on housing energy renovation and polluting heating systems. They can increase the cost of energy consumption through higher carbon prices. If poorly anticipated or implemented in a sub-optimal way, these policies can depreciate a household’s real estate assets, and impact its rental or sales income. Household vulnerability varies with income level and characteristics of the house (heating, energy efficiency).

Until now, national mechanisms have limited the transmission of risk to bank housing loans

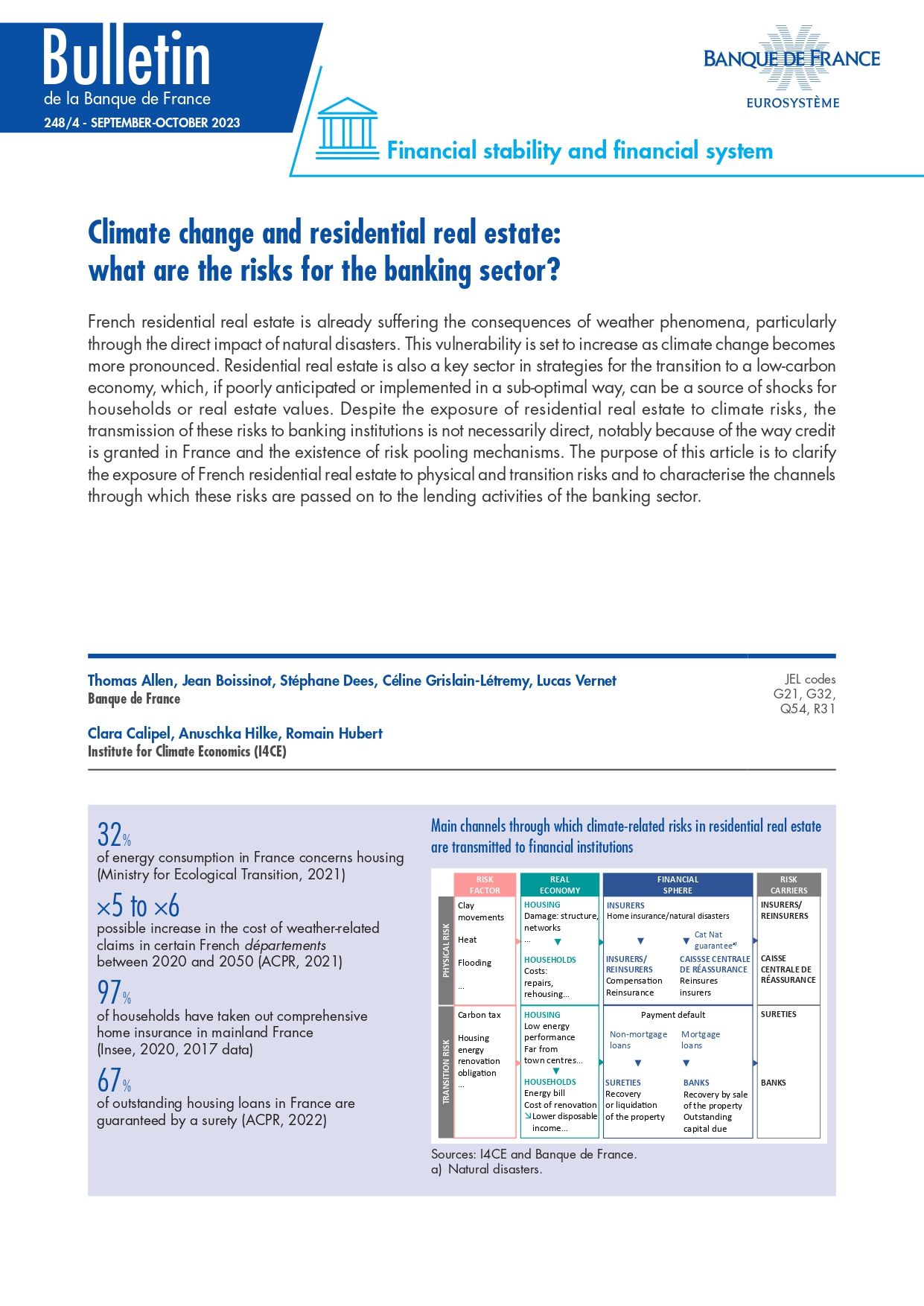

As explained in the box below, in the context of climate change, banks could suffer direct losses on their housing loan portfolios via a loss of households’ disposable income and a change in property value. However, a number of national mechanisms appear to limit the propagation of effects to credit risk.

How might climate and transition affect banks’ exposure to credit risk?

The main aspects of the “credit risk” exposure of a bank are borrower default, followed by difficulty in recovering the outstanding amount. The challenge is to understand how the climate might affect these two aspects.

Default may be linked, for example, to the loss of households’ disposable income, or to changes in property prices (e.g. if – as was the case in the sub-prime crisis – the borrower is able to deliberately stop repaying the loan when the outstanding amount exceeds the value of the property). Changes in property prices can also have an impact on the value that is recovered, since the sale of the property can serve as a basis for repaying the bank in the event of default by the borrower.

As mentioned above, climate change and transition policies can have an impact on the borrower’s disposable income and the value of the property, and therefore on the “credit risk” faced by banks.

Source: I4CE

In France, a specific insurance system makes a major contribution to limiting the exposure of housing loans to physical climatic risk, by absorbing the costs for households. The vast majority of French homeowners take out multi-risk home insurance, which includes compulsory “Cat Nat” coverage against natural disasters. The latter is managed by the Caisse Centrale de Réassurance (CCR), which receives a premium surcharge paid by households, and the guarantee of last resort from the State.

Lending conditions in France also help to limit climate-related real estate lending risk. For example, they are focused and demanding on income. This reduces the risk of default linked to a drop in income. The conditions also include a full right of recourse on the borrower, making it possible to decorrelate the value of the property from default, and difficulties in recovering losses.

The Crédit Logement guarantee mechanism also limits bank losses in the event of default. It includes a guarantee for banks, funded by all households taking out housing loans, and a specialized collection system.

In the current climatic and transitional conditions, the end-bearers of financial risk therefore appear to be sureties, insurance and reinsurance organizations, and ultimately CCR, for natural catastrophe risks.

The need to anticipate sustainability issues in the light of climate change

The context of climate change could lead us to revise this assessment of the sustainability of existing systems, and result in a change in the end-bearers of the risks, as suggested in the illustration below.

This is due in particular to the potential of climate-related issues to affect the socio-economic system as a whole. Mutualization mechanisms could be undermined by the unprecedented pressure that climate change is likely to generate: repeated and increasing shocks, that are simultaneous or closely spaced over time, as well as non-linear impacts, etc. The delay in adaptation and/or transition could also result in a more drastic adjustment later on, increasing the cost of transition for households (which could translate into an increase in their credit risk or a devaluation of their property assets) or even for public finances.

Against this backdrop, the ability of banks and insurance companies to devise and implement financing and insurance solutions that help transform the French housing stock regarding mitigation of, prevention and adaption to climate change remains the best guarantee of climate risk management.

This summary page has been prepared by I4CE and includes elements beyond the report available for download. This page does not commit the co-authors from the Banque de France, the Finance ClimAct Consortium or the European Commission.

This report is part of the Finance ClimAct project and was produced with the contribution of the European Union LIFE programme. This work reflects only the views of I4CE – Institute for Climate Economics. Other members of the Finance ClimAct Consortium and the European Commission are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.